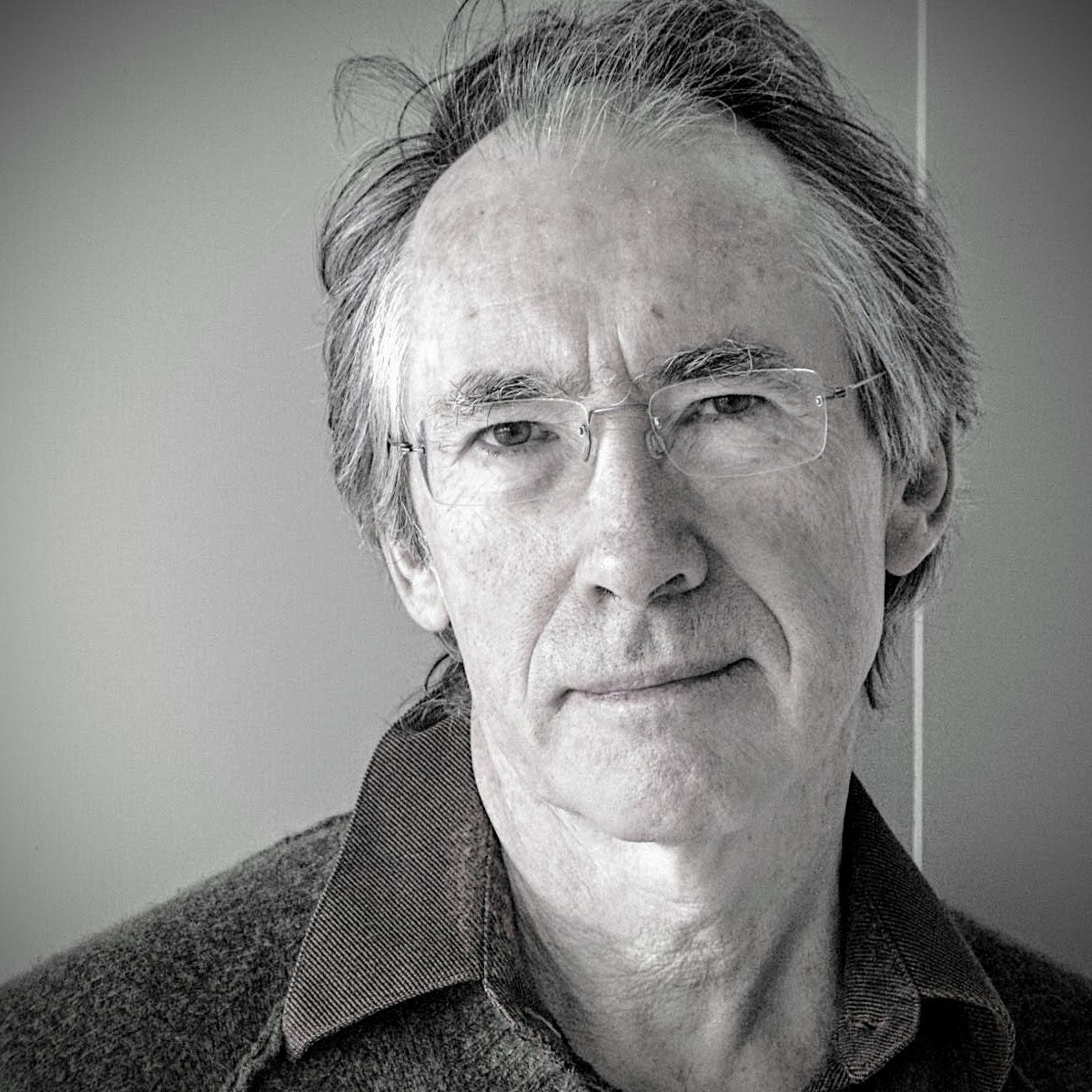

Ian McEwan: "AI will raise a mirror to what we are"

The author of Machines Like Me on moral androids and thoughtless humans

On the eve of Brexit, Ian McEwan was quietly – and eloquently – fuming. He was in Malmö for a reading at the city library, and as I sat down with him at the Hotel Savoy he had some choice words to share, about AI, about his countrymen, and about the state of the world.

Forty years ago he was a literary sensation, celebrated for his sharp prose and macabre fantasy. Since then, novels like Amsterdam, Atonement, Saturday and The Children Act have earned him the admiration of readers and critics alike. These days nary an article is written about him without burdening him with epithets like “one of the greatest writers of our time”. Still, now in his seventies, he is as vital, controversial and productive as ever.

His alternate history AI novel Machines Like Me was published in the spring of 2019, and in the fall he released another book, The Cockroach, about a bug (literal, crawling, six-legged little thing) who one day wakes up and realizes he has been transformed into a lesser creature: the prime minister of the United Kingdom, fully determined to push through a reform just as absurd and self-destructive – in the eyes of McEwan – as Brexit.

McEwan has confronted several thorny contemporary issues in his latest novels. In Solar, the climate crisis; in The Children Act, ownership of your own body; in Machines Like Me, artificial general intelligence. But Brexit has proven to be a scab he is particularly fond of picking at.

Shortly after the referendum, he wrote a piece in The Guardian about the barrage of lies, his dismay with the result, and the political intrigues that followed. He called the summer of 2016 “the summer of contempt”. When I ask him what he would call the summer of 2019 the reply cracks like a whip:

“The summer of bullshit.”

The Brexit question cuts deep, he says, touches everyone. For his own part, he has decided not to let Brexit ruin his friendships, but he has seen how friends and relatives – leavers and remainers – have stopped talking because of their disagreement.

“We’re full of self-doubt now, as a nation. We used to look at France with all its strikes, or at Italy with its 52 governments since the Second World War, the United States with Trump – there was a few months’ gap until the Brexit vote – and we thought that we were a practical people, empirical in our decisions, not carried away by abstract foolishness. We’ve really sunk in our own estimation and in the estimation of the world. We’ve become like a Shakespearean fool dancing on the world stage in cap and bells. It really has shaken us.”

How did you get so involved in the debate?

“It’s hard to avoid, really, It’s become this existential matter for the nation, what kind of country we want to be. And those of us who really wanted an outward facing liberal democracy that works with other countries are on the losing side in this struggle. It’s still a matter of wonderment to me that we’re doing something so pointless at so much effort, for so little gain.”

The Cockroach is not just a Brexit allegory, it is a also a satire of a particular type of politician, driven by narcissism, self-interest and complete contempt for the truth. And who – despite or because of all this – enjoys strong support among his voters.

“Boris Johnson has a very charming facade. I’ve met him personally, But his modus operandi has been ruthless, and really careless of parliamentary convention and legality. Proroguing parliament, closing down parliament for five weeks, turned out to be an illegal act. Everybody knew it was. He and his ministers went around lying into our faces, like old Soviet commissars.”

The heat only registers in Ian McEwan’s wording. He talks the way he writes, in a soft, neutral voice even as he passes merciless judgement.

“There was a way the Soviets had of lying, which you see now. It’s a tradition kept alive by Sergey Lavrov and Putin: they tell you a lie, they know that you know they are lying, and there’s a special kind of smirk on their faces. Now you see it in Johnson and you see it in his ministers. They went around saying the five weeks suspension of parliament has nothing to do with Brexit. Take that. You know I’m lying, I know you know, I don’t care. That’s the world we’re in now.”

What makes this type of politician attractive?

“That’s a good question. There’s a liberal guilt argument that goes ‘There’s a whole class of people that’s been left behind…’ I don’t buy that entirely. But there are some great failures of liberal democracy. One is incredible inequalities of wealth. We’ve seen, week after week, how some company fails and the directors leave with twelve million pounds. I think this makes people not only angry – they’re probably tired of being angry – but it makes them cynical. So all the best qualities of liberal democracy begin to seem like a mask, for this absolutely extraordinary corruption. So when they are asked to vote for the status quo or something else – which is basically the referendum – why vote for the status quo?”

Are you becoming cynical yourself, or do you look to the future with hope?

“I took some hope from the disapparance of Salvini in Italy. Austria had a good result. [N.b. this interview took place before the US presidential election in 2020.] But it’s not looking good at the moment. And it’s especially not looking good when we in this time of populism and nativism have a pressing concern of climate change, with which nationalism does not want to engage. Just when we need contries to pull together and do something rational, we have this big emotional surge that’s in quite a denialist frame of mind. That’s really unfortunate, it’s a perfect storm.”

While he seems to see the future clearly, Ian McEwan acknowledges that all our best – and worst – predictions may turn out to be wrong.

“We can look at the day to day politics and not notice that underneath it something else is moving. The world now is so complex and so connected that you can easily miss something else, something positive. The future is horribly fascinating.”

In Machines Like Me, humans are faced with a different kind of existential challenge than climate change. Adam, an intelligent android with an inhumanly rigid understanding of ethics, turns out to be ill-equpped to live among flawed humans.

Artificial intelligence has been one of McEwan’s interests for many years. At times he has been disappointed with the lack of progress in the field, but lately he has been encouraged by the progress in machine learning and the potential in quantum computing.

“I wanted to jump ahead, to what it would be like to have the ultimate, fully conscious machine. It’s a well-established theme in science fiction. You see it in Blade Runner and Westworld… Science fiction is probably the only fiction that has been thinking seriously about this. At the same time I always felt it wasn’t thinking intimately enough about what a close-up relationship would be with an artificial being.”

Machines Like Me is set in the 1980’s, on a parallel timeline where Alan Turing did not commit suicide but lived on to pioneer sentient robots. Demis Hassabis, the co-founder of DeepMind, is another prominent AI scientist that turns up in the novel, although in reality he was a child in the 80’s. McEwan mentions that he had Hassabis over for drinks one evening and had a chance to pick the DeepMind founder’s brain, informing his own view on the subject.

“The whole process of developing AI will raise a mirror to what we are,” he says. “I‘ve tried to imagine a moral machine that is superior to us, with fewer of our cognitive defects. Maybe it would hold positions that we would find challenging because we make allowances. We may have general rules like ‘You should obey the law’ and ‘You should never lie to the court,’ but you cut yourself some slack when it concerns someone you love. A robot may not do that. Telling lies is an important part of human interaction. Lies you tell to avoid wounding someone’s feelings or to protect a child against a truth theyre too young for – writing the algorithm for when to tell a white lie will be virtualy impossible, because it depends so much on being able to imagine what it is like to be that person. When robots can tell a white lie I would say we have to say they’re conscious.”

With consciousness comes questions about human (robot?) rights. A potentially exponential increase in synthetic intelligence, which may be the effect of a superior intelligence learning to improve itself, gives rise to existential questions about what humans should really be doing with their lives. Scientists and philosophers have even warned that the survival of the human race may be imperiled, as these machines may see us as obstacles to their goals.

Maybe humankind can finally unite once we are faced with the threat of being rendered superfluous by artificial intelligence?

“The threat is there already, but we can’t stop ourselves. There is such massive economic advantages to nations with highly developed AI systems for agriculture, for logistics of delivery... Even as Stephen Hawking was saying this is a greater threat than nuclear weapons or climate change, nothing can stop us, as we live in a competitive free-market world. More than that, we’re fascinated by creating something more intelligent that ourselves. It has a semi-religious quality. Not only do we want to be God and create the perfect being, but that we want the friendship of a super-intelligence, which was always what religion was offering.”

With Adam, they are fascinated by his growth and development, but in the end he does become a threat and they have to deactivate him…

“But they can never get rid of him as he can upload elsewhere. In his parting speech, which is my nod toward the final act of Blade Runner, he bascially sends a love letter to humanity, saying ‘We are immortal and you are not. I don’t say this with any pleasure but with great regret. Getting to know you but knowing that you must die fills me with great pain.’”

Should we worry more about artificial intelligence or human folly?

“Well, it’s human folly that is going to be designing these machines, so we better watch out! Which is why my machines, one by one, start to close down their consciousnesses. Because of all the contradictions. We humans say we love life, we love the forest, yet we set fire to them. Et cetera. It’s just too much for them.”

Ian McEwan does most of his writing in Gloucestershire, in an old barn converted to a study. But finding the peace of mind to write is not trivial in a hyper-connected world.

“One of the things we’ve lost with the internet is solitude. This toy that we carry around, it’s so irresistible.” He holds up his mobile phone. “I’ve noticed traveling recently that when you get off the plane and you go to the luggage carousel and you know the luggage isn’t coming for ten or fifteen minutes, previously you might go into your thoughts. Now you go into your emails and text messages. There’s less daydreaming of the free-floating kind. In the past I could easily just take a walk around my mind, waiting for the luggage. Memory, desire, imagining, calculating, rehearsing – all the kind of things one does. Yet my curiosity is great, so if there’s no email that needs my attention, I go on the news or the texts or Whatsapp.”

He says he could be content never writing another word of fiction, spending his days reading the news and answering emails, fully enthralled by the 24 hour news cycle and the constant nudges of apps and people wanting him to do this or that.

“It’s a wonderful machine, but it’s quite invasive and addictive. I held out against this, I had a snap phone even as they were becoming things in museums. Because I noticed that everywhere I went, people were staring at their screens, all the time. I thought I will never be like that. And then I found that if I was away for two weeks I would come home to 400 emails…”

When you see the eerie scene of a room full of people hypnotized by their screens, you can’t help but think that if an AI were to take over the world and subjugate us to its will, this is exactly what it would look like.

“You worry about subjugation – but it has already happened! On the other hand people are communicating with each other, even if they’re not in front of each other. We’ve dissolved geographical space. They’re mostly in touch with others.”

Despite the distractions, you still manage to write.

“I do, because I can switch it off. My wife has this program called Freedom.” He refers to an app that switches off the internet connection so a writer can focus intently on their text, interruption-free. “Do you use it?”

No, but I probably should.

“That’s what I think. But maybe I don’t like the possibility of freedom. Maybe I’m scared of freedom.”

I get the feeling that you are free in your writing lately.

“Yes. I’ve slightly unshackled myself from realism. I never set out to do that, it wasn’t a program. Having done it once with Nutshell, people asked me if this was a new direction and I had no idea. But it is, slightly. Both Cockroach and Machines Like Me are slightly unhinged from my past, when I was writing strictly within the laws of physics. It feels to me like a release.”